Delhi’s Pollution in 2021: a five-minute roundup.

Photo: Reuters

Researchers from Harvard university have estimated that about 2.5 million people die too early every year due to toxic air in India. This is just the latest in a long line of reports and news sounding the alarm on air pollution’s insidious impacts, from obvious illnesses like asthma and heart attacks to potentially surprising health disorders like deteriorating bone health and potentially irreversible eyesight loss.

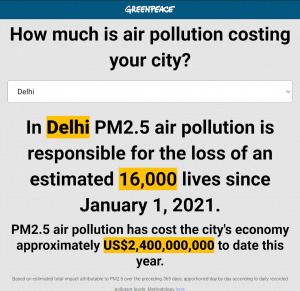

Nowhere else is the conversation about polluted air more centered than in Delhi, whose residents have to breathe thick, dust and smoke laden air nearly all year. The Greenpeace report estimates that 54,000 people died of excess air pollution in Delhi over the year 2020, and pegs economic losses at 8.1 billion.

LocalCircles conducted two surveys gauging public opinion about air pollution across five cities in the Delhi NCR area. The first in October 2020 got 15,000 responses, 65% of which said at least one of their family members is suffering from pollution ailments (asthma, etc). The second in November got 35000 responses, of which 73% said the same.

Other surveys found that 40% of respondents said they would move out, while a significant percentage would “just live with it” and eat more immunity-boosting foods to protect themselves. Clearly, Delhi’s residents are between a rock and a hard place: either upend their lives or suffer in the smog.

"Odd-Even Rule"? More like...an "Odd Rule"

Of the measures taken in the city to curb pollution is the well-known “odd-even rule”, which allows vehicles within license plate numbers ending with an even or odd digit to ply on roads on alternating dates. Experts are divided about whether it succeeded in reducing pollution. After the 2016 pilot, a statistical analysis by EPIC-India estimated that the Odd-Even rule reduced pollution by PM 2.5 (the pollutant considered most dangerous to health) by 13% overall, with most reductions seen during late morning hours and in the month of January, rather than April.

However, another analysis conducted by Current Research – which included other pollutants like VOCs and aromatic compounds – concluded that The Odd-Even rule might actually have increased pollution levels, because people may have chosen to commute earlier before the rule was enforced for the day. Moreover, the numerous exceptions granted to vehicles of a certain type (e.g. two wheelers), a certain use category (taxis, government service vehicles), and based on the driver’s identity (female drivers) didn’t help its cause.

Photo: PTI

Dr. Santosh Harish, who co-authored the EPIC study, advocated for the odd-even scheme for use as an emergency measure especially in the winter months. But others are more critical, saying given it’s marginal effects it might as well be disregarded. The two views aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. Delhi could well do with an odd-even scheme, but implemented sparingly and with force when it is most needed.

At the same time, It’s safe to say any positive impact that the Odd-Even rule has will steadily decrease as any remaining COVID-19 restrictions are lifted and ever more fossil-fueled vehicles are bought and driven on Delhi’s roads. So some energy surely needs to be redirected towards enforcing more targeted, long term pollution control regulations like congestion charges, and low emission zones.

Electric vehicles: much hype, but little trust

There is also a significant move towards Electric Vehicles, both on the national and state levels. Schemes to boost investments in electric vehicle manufacturing, such as FAME, began in the latter part of the 2010s and are being implemented through this decade. Automobile giants like Tata have launched four wheeled electric sedans and SUVs, and the three-wheeled electric rickshaws are also being rolled out in multiple cities. But given concerns about recharge time and mileage, the EV industry has ways to go to convince the everyday consumer to leave behind cars fueled by petroleum.

Graphic: GoMechanic

In the public transport sphere, there are ambitious plans to electrify buses. In 2019, the Delhi Transport Corporation ordered 1000 electric buses, 300 of which will be phased in from late 2021 onward. However, mismatches in financial expectations and trade constraints brought about by the coronavirus pandemic – have hamstrung this process. In response to an RTI filed by Jhatkaa.org in December 2020, the Delhi Transport Corporation disclosed that for none of the three tenders filed during late 2019 to early 2020 did bidders qualify for electric bus orders.

Stubble burning: an unlikely scapegoat

Aside from vehicles, the most popular reason for Delhi’s inhospitable air is the smoke wafting into the city from neighbouring states Punjab and Haryana in the onset of winter, when farmers burn the stubble left on the ground after they harvest their summer rice crop, to make way for their winter wheat crop. Farmers used to burn stubble closer to the end of summer in September. But a law passed in 2009 delayed the summer cropping season to save groundwater and brought the summer harvest brought it too close to the winter season. With little time left to clear the field, and a lack of labour or machines to help, the farmers began burning the crop.

Though it is easy to identify those responsible for stubble burning it’s not so easy to hold them accountable. Stubble burning cannot be looked at in isolation from the laws and economic conditions that have allowed it over decades, and therefore needs to be dealt with using arguably more complex and nuanced measures than, say, those for decarbonizing transportation.

Dr. Harish, who is working on this issue at the Centre for Policy Research, said a crop shifting approach needs to be developed over the long term so farmers can reduce their dependence on a lucrative but water-intensive rice crop they grow. Combining that with, first, a price support and guaranteed sales for other crops like maize, and second, subsidies to mechanized harvesters that can weed the stubble out, might do the trick.

Photo: Neil Palmer (CIAT, Wikimedia Commons)

In a nutshell: Delhi chokes because of an overwhelming demand for dirty energy and transport, a poorly-planned waste management system which causes garbage burning, and an unfortunate geography and climate that traps pollution from within and without the city. A problem this complex requires more than one solution, including reliable zero-emissions public transport for residents, better crop management practices for farmers in neighbouring states, and thorough waste disposal.

If you liked this explainer, click on the button below, read, and sign our petition to get old, polluting vehicles off the streets of Delhi. We think this is a relatively simple but effective solution that seems to be ignored by most.